Review by Carole Mertz

Review by Carole Mertz

Motherland moves me more than any poetry I’ve read in recent months. Through Sally Thomas’s lines we experience Life as God’s sacred offering to us, and ordinary living, a kind of sacred offering in return. This giving and receiving, both ordinary and extraordinary, is present in almost all of Thomas’s poems, no matter what poetical form the author chose. (She uses the sonnet, sestina, villanelle, and other forms.)

A memorable poem opens the collection. Thomas presents “Change-Ringing” (3) in six beautifully rhymed quatrains; the subject, a woman, recalls a time of nursing a child. The ringing of the church bells (“a wordless shape-note singing”) resounds through the poem, as the mother holds the child through “the sigh and suck,” and through the clamor she’s “caught by the memory’s glamor.”

In “Lamplight” (59) the narrator has stepped outside and stands viewing her house at night. The poem expresses a gentle domestic contentment. The second stanza follows:

Leaked lamplight, a gold spill on the dry

Black stalks of black-eyed Susans beneath the window.

Behind its veil, the room shone privately

As with a happiness, a mystery to me.

I stood outside and wondered at that glow.

“Angelus” (8), a poem pregnant with anticipation of future children is written in second person; the persona imagines the awaited children as dresses hanging in the closet “timeless, never out of style. One of them could choose you.” Using a sacred evocation, she speaks the words spoken by the Biblical Mary, “Be it done to me, according…”

Another remarkable poem, “Morning, with Goldfinches” (37) offers six stanzas of fourteen lines each. The final line of a stanza becomes the opening line of the next. The rhyme scheme is sustained with delicate rhyming reverberations, as when “curtain” rhymes with “when,” “molt” with “throat,” and “plenty” with “flinty.” Spring comes with “trees in flame like angels,” Thomas tells us, and “Sweet brevity, newest hour, everything most lovely, most loved, goes singing.” With such fine lyricism, we feel as if we, too, want to sing as we await the coming of spring.

Throughout the collection, Thomas’s sure control of poetic form, rhyming, slant rhyme and enjambment techniques is constant and consistent. Many of the poems depict instances of domestic life, memories of family members, the intimacies of married life; but on page 77, she shifts into a final segment.

The twenty poems in the “Richeldis of Walsingham” segment, the most numinous of the entire collection, relate to an ancient shrine in England, destroyed during the reign of Henry VIII, then rebuilt as a Roman Catholic shrine in 1934. These poems use double titles, given in English and Anglo-Saxon. Often they reference specific years. They allow the reader to traverse through a long period of English history, both its language and happenings. Through them, Thomas presents a predominantly mystical view of the world and its future. “Stangefeall (fallen stones),” for example, speaks of a quiet wood: “It’s quiet there, and old. / In the bluebell woods, silence / speaks in tongues.” (81) And “bidden”(to pray)” is beautiful in its solemnity:

There is the lick of Lauds-bell, the wind’s weeping.

Biddan: Ic bidde. We bidden.

Bed-making. Bidden, the soul’s housewife sweeps

Clean the clod-cold hearth, furnishes fire

To see by, with sighs more wordful than words. (77)

Again, through Thomas’s well-chosen words, we experience the sacred element of the ordinary and extraordinary in her beautiful Motherland. It’s a volume to hold close for years to come.

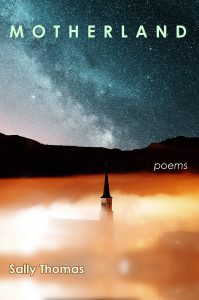

Motherland by Sally Thomas

Able Muse Press, 2020

$29.27, Hardcover $18.57, Paper

9781773490434

Carole Mertz, poet and essayist, reviews for various journals including Copperfield Review, Dreamers Creative Writing, Eclectica, Main Street Rag, and frequently for Mom Egg Review. Her own poetry is newly released in Color and Line, her first full-length collection. (Kelsay Books, 2021). Carole is a semi-retired musician who, to remain healthy and hopeful, began writing poetry some years ago.