Review by Barbara Ellen Sorensen

Review by Barbara Ellen Sorensen

A definitive theme in Margo Taft Stever’s new volume of poetry, Cracked Piano, is the mercurial role of mothers. That motherhood is both a terrifying and transcendent time in many women’s lives is not lost on Stever. Over and over, the poet sketches images of women who don’t just model binary traits of good and bad but who are fully realized human beings. Children and infants inhabit the poems as well and motherhood is filled with the vestiges of childhood from eating animal crackers to feeding puppies. These are unfailingly light images embedded in dark poems where “Even the known becomes unknowable” (68).

Through achingly beautiful lyricism Stever almost immediately informs us how as a society we are constantly misstating the role of mothers. The poet notes that as adults we forget everything our mothers did for us and instead we focus on “the deprivations—/that I cannot cook,/that I never fed you” (7).

Buried deep in our unconscious, also, is a myth that stubbornly persists—the myth of the evil stepmother. In the eponymous poem “Stepmother,” the negative stereotypes are noted, “A stepmother is always bitter,/rash, always seizing the rice,/the beans …/A stepmother is always evil,/marked by the blood of her husband’s children” (10).

In the poignant, “My Mother is Dying,” the poet wrestles with the terrible angst that comes with recognizing that when a parent dies, no matter how old we are we become unmoored: “Wandering once again, now I/return to the center, searching/the level earth, calling her name/remembering that I am lost” (14).

In the second section of the book, Stever sets out to tell the story of her great-grandfather who was most likely misdiagnosed with a mental illness and confined to an asylum. Yet in the haunting “The Lunatic Ball,” motherhood, though turned on its proverbial ear, is never far from the poet’s searing pen, “A woman names her baby doll Christ, lurches,/leans, a building in an earthquake, then/she crawls.” (19)

Stever’s musings are stark and unrelenting. As readers, we are doused in the realization that we are stuck on, “…A train of thieves, all of us/who never cared for our jobs or our mothers…/

In the poem, “Quiet, with Trees,” Stever slyly implies that for all of the inevitable failings, most mothers shelter us from calamity and, “The child clings to you/as branches crash/onto the sidewalk” (53). The tenuous universe can rob mothers of their children and if a mother loses her child, “a fearful fear” (68) will grip her heart forever. In “Receiving the Ashes,” Stever writes, “She stood on the sidewalk./Her small boy looked down,/plumbed the depths of the storm sewer./She looked away for a moment,/and when she looked back,/she could hear him far below./…She had nothing to hold onto” (59).

In “Bottomland,” Stever observes and writes, “How a mother can change from angel/to sour mudqueen of all decay” (68). Though this could be interpreted as simply pointing out the ambiguous nature of mothers, in the end, the poet instructs us to “remember your mother,/a mother who loved her children” (68). A mother is a not a caricature, she is fully developed human being. This is the lesson that is culled from the “estuary of the deep” (68) and Stever has rendered it unforgettably.

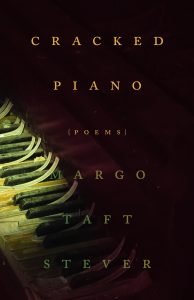

Cracked Piano

Margo Taft Stever

CavanKerry Press, 2019, 79pp [paper]

ISBN: 978193380709

Barbara Ellen Sorensen is former senior editor of the American Indian Science & Engineering Society’s flagship publication, Winds of Change. Sorensen is a contributing writer to the Tribal College Journal. Sorensen has had three books of poetry published: Songs from the Deep Middle Brain (Main Street Rag, 2010), Compositions of the Dead Playing Flutes (Able Muse Press, 2013), and Mary’s River (Kelsay Books, 2018). Her first book was nominated in 2011 for a Colorado Book award.