Lara Lillibridge

Lara Lillibridge

On Writing Mama, Mama, Only Mama

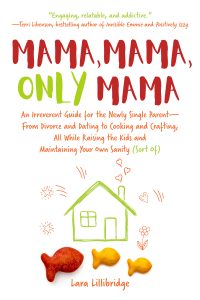

Lara Lillibridge on her memoir, Mama, Mama, Only Mama: An Irreverent Guide for the Newly Single Parent—from Divorce and Dating to Cooking and Crafting, All While Raising the Kids and Maintaining Your Own Sanity (Sort Of).

(Skyhorse, May 2019)

Being a single mother means relaxing your cleanliness standards. A lot. Being a single mother means missing your kids like crazy when your ex has them, only to want to give them back ten minutes after they come home. Being a single mother means accepting sleep deprivation as a natural state. Being a single mother means hauling a toddler, a baby, and a diaper bag while wearing high heels and a cute skirt, because you never know when you’ll meet someone. Being a single mother means finding out you are stronger than you ever knew was possible.

I always knew I wanted to write someday—that elusive wisp of intention without the needed passion to bring it to reality—but I had nothing to say. Then I got pregnant with my second child, and suddenly I was flooded with stories. I wrote every minute I could while staying home with my eldest, who was two years old. I woke up in the middle of the night obsessing over word choices and plot lines and how much setting was really necessary. Writing was something I could not stop doing.

Then I left my husband, and built a new life for myself and my two children—both still in diapers. I wrote passionately but less frequently, reworking the same essay over and over, but making little forward progress. I worked two part-time jobs and enrolled in school to finish my bachelor’s degree. One of my classes required that I create a blog, and I found a new voice and a new medium. When I graduated, I committed to myself that I’d blog three times a week for a year.

The Only-Mama blog was where I developed a consistent writing habit, and writing regularly improved my sentences. But it was also where I sharpened my eye for how to tell a story concisely and with humor. Many stories can be told humorously or tragically, and looking out for a funny story helped me see my kids and myself in a happier light. I wrote my way into seeing our life with rose colored glasses. As a person who has struggled with depression my entire life, this was a monumental shift in thinking. Blogging made me live in the moment, observing my family, instead of being lost in my head. It made me a better mother.

I posted 184 blogs that first year, but then I started grad school and fell away from it. I immersed myself in “serious” essay writing. I had two voices, my blog voice and my essay voice, and my advisor told me that when I was able to merge both voices into one piece, I’d have found my true voice.

During this time, I wrote my first memoir, Girlish: Growing Up in a Lesbian Home. It was literary, it was experimental, and it was very dark. While I was querying Girlish, I started fleshing out my blogs into a book, expanding posts and filling in the spaces in-between with new material. It was fun, light—a warm quilt after the emotional devastation of writing the first book. I amused myself with it, inserting survivalist recipes for things like s’mores casserole or instant oatmeal cookies between the chapters. Pretty soon I had a book with some shape to it. My publisher was interested in Mama, Mama, Only Mama, but I had to wait for Girlish to come out before they’d put it on the schedule.

I didn’t want to wait, but I needed to. The experience of publishing Girlish changed Only Mama. I realized that I couldn’t be naked in book one and flippant in book two. Even though Only Mama wasn’t meant as a sequel, it was likely that fans of Girlish would read it, and I didn’t want to disappoint them. I wanted Only Mama to be not just funny but also resonant, and that meant I needed to add the shadows behind the laughter.

I had a bunch of essays from my MFA that I didn’t use in Girlish. I started folding some of those pieces into Mama, Mama, Only Mama. It was hard. The voices were pretty disparate at first. I had to rework a lot of things to make them blend, and add in completely new chapters to bridge the blogs with the essays. In the end, it was more honest, and I hope, more beautiful.

Excerpt: Step Stools

Everyone wants to know why my marriage ended. It’s a natural curiosity, I suppose, but it’s not a question I want to answer. There’s the easy answer, and the hard answer. Easy answers are all about what he or I did or didn’t do, but they always end with, “yeah, but couldn’t you have tried harder?”

Then there’s the hard answer, which takes time to understand in my own head and longer still to codify for everyone else. Still, I should have an answer. Whether others find it satisfying or not is irrelevant.

To say why my marriage failed, I have to first talk about a pair of step stools of the same approximate size and shape. One is pale green, the color of a tulip stem. Made of lightweight, molded plastic, its design is clean, simple, functional. As far as step stools go, it is perfectly adequate. The other step stool is old wood, long ago painted red but now covered with paint splatter from other people’s projects and also a few of my own. I can- not tell you why I had to buy it at that garage sale last summer, the one we walked to around the corner, where my youngest child bought a mini tape recorder and I found so many things that pleased me that I left with my arms overflowing. The red step stool was only one dollar, but I would have paid five or even ten dollars for it, even though I already had a perfectly adequate step stool at home. I couldn’t live with new molded plastic once I found old wood painted red and worn in spots by years of other children’s feet.

My ex-husband is a good man, but he will always choose the pale green step stool the color of tulip stems and our cat’s eyes. When he looks at the old red wood stool, he sees only junk past its prime and destined for the garbage heap. When I look at the green plastic one, I see only cheap, prefabricated func- tion-over-form nonsense. I told him when we met that I liked the plastic one better, that I wanted new and clean and functional, and I wanted to want that, I really did. But I woke up one day and saw that there was no old paint-splattered wood anywhere and I couldn’t live like that anymore. There was no room for worn-down red in our fresh, new, and functional tract home filled with soft beige and ivory and a dash of pale blue.

My ex-husband will tell you that one day I woke up and had gone crazy, and nothing worked right after that no matter how hard he tried. His ver- sion is also true. What can you say to someone who sees old paint-splattered wood as junk without sounding crazy? How can you live without old wood and not become crazy?

When I go to my ex-husband’s house now—the one we bought and furnished together—little has changed in the five years since I left. I left no lasting impression; I painted no walls, hung no art. That’s not true. I sewed the throw pillows on the couch. I hung the posters in the playroom, the ones his sister sent. But what I did was so anonymous and bland it could have been done by anyone. I can’t believe I ever lived like that. When my ex comes to my house—the one I have lived in for the last five years—it is overflowing with chaos and toy splatter and half-finished projects. He can’t imagine anyone would want to live like this.

Lara Lillibridge is the author of Mama, Mama, Only Mama, Girlish: Growing Up in a Lesbian Home, and co-editor of the anthology, Feminine Rising: Voices of Power and Invisibility with Andrea Fekete. Lara Lillibridge is a graduate of West Virginia Wesleyan College’s MFA program in Creative Nonfiction. In 2016 she won Slippery Elm Literary Journal’s Prose Contest, and The American Literary Review’s Contest in Nonfiction. She is a reader for Hippocampus Magazine and judged AWP’s Intro Journals Award for 2019.