Review by Judy Swann

One of the ways people respond to revolution in the arts is to ask, “But what does it mean?” Laurie Anderson, Alison Armstrong-Webber , Miranda July, Lily Gershon, Phillipe Petit, Raymond Queneau, and Gertrude Stein all got asked that question. And I’m sure Jessy Randall gets it too. So, it’s worth asking ourselves how much meaning matters. I personally feel that “meaning” in the commonly held and strictly denotative sense of “prose-equivalence” is over-rated. I wouldn’t call Jessy Randall’s diagram poems irrational, but they do not convey meaning the way, say, a number does or the way that Chaucer did to the English nobility of his day. Randall’s How to Tell If You Are Human splits the atom of consciousness; it challenges the reader aesthetically and it exudes intellectual comfort. In short, it fundamentally mirrors the growth of our inner beings.

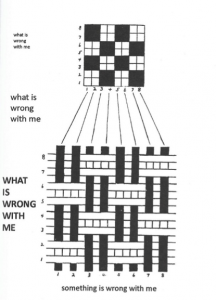

If you’re recently out of middle school, the excruciating self-censorship of youth will still be in the full flush of its resonance in you. Moreover, it will still be resonating with you even if you’re approaching retirement – whether or not you’ve made your peace with it – because no one really survives their teen years unscathed. (Or do they? Is it really only me and Jessy Randall who suffered?) Using the top-most words to name her unnamed poems, I give you Randall’s take on that in her piece “what is wrong with me” 71:

Moment by moment, Randall co-locates Looking at, Being in, and Thinking of. She doesn’t organize thematically as is the more traditional path. The subject of “what is wrong with me” is not sitting in a roomful of peers, feeling left out, making explicit parallels, or narrating her lived experience to help you identify with her. The subject looks at an ordered grid, she re-orders it, she poses her question. She lets the reader decide how much work to put into it. The original image for “what is wrong with me,” by the way, is from Mary Schenk Woolman and Ellen Beers McGowan’s Textiles: A Handbook for the Student and the Consumer.

Randall takes the question of y/our ineptitude and holds it up against the wonders of the world. She does this thanks in no small measure to the wonders of the Colorado College Special Collections, where she works. I give you “I am trying so hard not to turn into my mother” 61:

What universe exists independently of our mothers? This base image here is from George Henry Lepper’s From Nebula to Nebula.

Randall does not do ekphrasis, which is the rhetorical or poetic figure wherein a visual object is described in words. She’s not doing art criticism. Even with an extension to the limits sometimes given the term, most of the images that elicit Randall’s response wouldn’t be called art. They are, for the most part, textual figures. Take “in a meeting” (p. 60) that looks like Charles Darwin’s whiteboard of his argument for “Probable effects of the action of natural selection through divergence of character and extinction.”[1] Some threads are productive, some are not. Actually, the uninflected image for “in a meeting” is credited to Naomi Sager’s Natural Language Information Processing: A Computer Grammar of English and its Applications.

This source file is from one of the newer old books Randall mines, copyright 1981. The majority of books Randall cites in How to Tell If You Are Human are from earlier in the last century. Some are color, most are black and white. Some spread across two pages, some are complete in one. All are enriched by Randall’s attention.

If you believe that art is long, pleasure is good, and the revolution is upon us – you will love How to Tell If You Are Human!

[1] Unlabeled diagram, p. 121. Charles Darwin. The Origin of Species. New York, Collier Macmillan, 1962.

How to Tell If You Are Human by Jessy Randall

Pleiades Press, 2018

ISBN: 978-0-8071-6984-1

Judy Swann is a poet, essayist, editor, and bicycle commuter, whose work has been published in many venues both in print and online. Her book, We Are All Well: The Letters of Nora Hall has given her great joy. She loves. She lives in Ithaca, NY.