Review by Issa M. Lewis

Review by Issa M. Lewis

Any creative writing teacher will tell you that conflict is at the heart of fiction; stories require dissonance, tension, to capture our attention and help us connect with the characters. Alex Behr’s Planet Grim doubles down on that well-worn tenet with stories that illustrate the convolution of human nature.

Behr’s characters feel every twist of their lives as a sucker punch. For example, in “The Courtship of Eddie’s Father,” the speaker is a husband and father of an adopted infant son. While he feels overwhelming love for his child, he is conflicted about his relationship with his wife, which snowballs into infatuation for Eddie’s birth mother:

And now, Crystal in the flesh, on the park trail headed toward us. I stand too quickly and bang my knees on the edge of the picnic table. Eddie’s snug in a striped onesie, stuck in a front-facing baby carrier and all I can focus on are Crystal’s cutoff jeans and black hair. “Hi, Mommy! Hi, Daddy!” she calls, as if speaking for Eddie—her son/our son. She’s been trained well by the social workers. She puts the baby carrier on me, adjusting the straps. She’s close. And I stiffen, awkward, almost rude. I do a hug that pushes her away. Eddie’s between us. He mews—squished—and I picture kissing her and putting my hands down Crystal’s pants, lying beside her on the grass and tracing my tongue on her C-section scar. (34-35)

The conflicted father knows his feelings are inappropriate, and yet tries to rationalize them by considering how arduous the journey to adoption had been, and the rifts it made (or at least that he perceives it made) between him and his wife, and within their extended family. This passage is also an excellent example of Behr’s skillful use of short, clipped, declarative sentences that speed up the pace of her narrative and provide a level of urgency that the reader can share with the characters.

Behr’s explorations of the human condition are not limited to earthy reality—literally. True to the collection’s title, Behr takes us to landscapes beyond our own planet in “My Martian Launderette.” The protagonist, Troy, works at a laundromat on Mars, which has been transformed into a mining colony by NASA after earth’s most fertile mines have given out. In this imagined future, it appears humans are once again laying waste to whatever planet they inhabit, stripping and scorching in their search for natural resources. Most of the people on Mars are ill from the byproducts of mining—even people like Troy, who does not actively work in the industry.

Most intriguing in this new world are the measures taken to prevent sexual assault: red buzzers that deliver electric shocks to men who press them. Behr writes:

Troy gripped his broom. He shouldn’t touch her. He needed to. He shouldn’t. It would be painful. The men needed taming on Mars, like anywhere, so to lure women to the planet, the colony leaders had installed electroshock machines. Men had to press red buttons if they couldn’t control their base impulses. The leaders threatened men with expulsion to one of Mars’s lumpish moon, like being sent to rot on a potato. (113)

The women in Troy’s life force him to press this button even for innocuous offenses, or else threaten him with it if he gets too friendly for their comfort. This also serves as an example of an overarching theme of sexuality throughout Behr’s prose; however, it is not sex for love, but sex for lust, sex for gain, sex for appeasement—even sex to fulfill other unmet, and maybe even unidentified needs.

To that end, Behr admirably does not shy away from uncomfortable topics. Even in the opening story, “White Pants,” she begins with the story of a character’s middle school embarrassment when she begins to menstruate in the middle of the school day. Likewise, in “The Shrew of D.C.,” she covertly approaches the character of Monica Lewinsky during her time as former President Clinton’s mistress. Behr unapologetically paints pictures of people who do not shy away from the distasteful, taboo, or ugly aspects of their lives; in fact, some, as “M.” does in “The Shrew of D.C.,” embrace it:

Now, while on hold, she looked down at her dress, the one she could barely afford to have dry-cleaned, at the splotches of dried cum. His sperm tasted like a mouth full of buttermilk and heat, and she often kept it in her mouth and pressed her tongue against it. She tried to taste the spot on her dress, but her finger tasted of salty chips. (134-135).

In all, Alex Behr’s Planet Grim is an honest exploration of human conflict, convolution, and confusion. Her pacing, unflinching gaze upon the grotesque, and her unique descriptive turns make this book a gripping and compelling read.

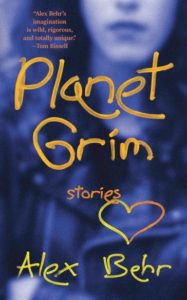

Planet Grim

by Alex Behr

7.13 Books, 2017, $15.95 [paperback]

ISBN 9780998409221

Issa M. Lewis is the author of Infinite Collisions (Finishing Line Press 2017) and a graduate of New England College’s MFA in Poetry program. She was the 2013 recipient of the Lucille Clifton Poetry Prize, and her poems have previously appeared in Mom Egg Review, Tule Review, Jabberwock, Blue Lyra Review, Pearl, and Naugatuck River Review.