Review by Grace Gardiner

Review by Grace Gardiner

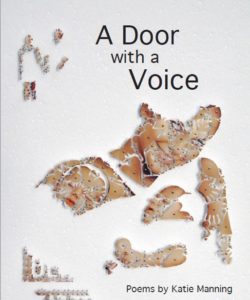

At first glance, the premise of Katie Manning’s fourth collection, A Door with a Voice, a free digital chapbook available for download from Agape Editions’ Morning House series, seems simply and obviously rendered. Manning, the founding Editor-in-Chief of Whale Road Review and an Associate Professor of Writing at Point Loma Nazarene University in San Diego, prefaces the chapbook’s sixteen poems with an artist’s statement that outlines her process of composition whereby she “us[es]the last chapter from one book of the Bible as a word bank for each poem” (iii). Furthermore, the contents page pairs each poem with the biblical book from which its words were lifted, and each poem appears with the phrase “all that remains of X” beneath its title to indicate again which book serves as “word bank”—a kind of dedication and attribution and epigraph all rolled into one. The poems’ titles, too, are anagrams that mirror the Bible’s own naming principles. Thus, Ruth becomes Manning’s poem “The Book of Thru”; Song of Songs becomes “The Song of Sons”; and First Thessalonians becomes “The Book of This Season.” There is an honest effort by Manning to ground her reader in the impetus of her material, to pair explicitly the stream and its headwaters. This move, which some might critique as repetitive or redundant, even heavy-handed, balances the complex and elliptical work at the center of the collection’s poetics: erasure, lack, and the contradictions of language as their own kind of communicative power.

Consider the opening to the chapbook’s first poem, “The Book of Evil” and “all that remains of Leviticus”:

make

a person

a male

a female

a person

a male

a female

a person

a male

and

a female

of silver

a person

or more

a male

a female (1)

In one way, the streamlined quality of this poem, in its shape and fairly consistent monometer, speaks to the manner in which such canonical religious texts like the Bible are excerpted and extracted not only from their original contexts and literal pages but also from their exceedingly nuanced compositional histories, which include at the very least a mixing-pot mess of sanctioned and unsanctioned source materials as well as the various and varied translations and mistranslations of these texts. Manning acknowledges and admits to this larger commentary in her artist’s statement at the chapbook’s beginning, “I am tired of people taking language from the Bible out of context and using it as a weapon against other people, so I started taking language from the Bible out of context and using it to create art” (iii). This revisionist attitude which makes to illuminate the flaws of a certain text by enacting that text’s same flawed practice is thus evident in Manning’s own extreme excerpting of the relational complexities of syntax and morphology, of clause and phrase, of language itself in these clipped lines.

Nevertheless, Manning’s selection of words directly opposes those who would use their own selection “as a weapon against other people” in its proliferation, not reduction, of meaning. Often in poetry and in the act of writing in general, there is the accepted principle that the illustration of the specific breeds in the reader an understanding of the universal. Manning’s specific word choices, then—her extremely concentrated diction—place her readers in a wider and more navigable mindset. Her vision transforms its lack into a want or need, a desire to explore, not a deficiency nor capitulation.

It’s important to note, too, that Manning’s own compositional history is anything but obscured in this collection. Indeed, if one compares the above stanza of “The Book of Evil” or the opening of “The Book of Is”—“heaven is my / foot // where is / my hand” (10)—or the ending to “The Book of Thru”—“he was the father of / the father of / . . . / the father” (5)—to their source materials (Leviticus, Isaiah, and Ruth, respectively), they will find that Manning has not just devised a “word bank” from each book’s last chapter, but an ordering, too, so that her poems read as transposed erasures. Manning does not only take the Bible’s words “out of context,” but its own structural and rhetorical power, too, an act which makes the distinct and unorthodox imagery of such poems as “The Song of Sons” even more pronounced and palpable:

a

breast

is a door

with

a

voice

let me hear (9)

One critique that might be leveled against A Door with a Voice is that the collection can’t stand alone or apart from its source material, that the collection uses its intellectual ekphrasis of sorts as a crutch and handhold and therefore these poems’ resonances are limited to what they are compared and contrasted against. Yet Katie Manning could have easily obscured the collection’s origins and left it to those exceptionally familiar with the Bible and its passages to make some semblance of a connection. Instead, she opts for an accessible deconstruction of language and tradition out of which readers can participate themselves in a new building of meaning. For, though we are individuals separate in body and mind from one another, we never really stand alone or apart from our histories, our lineages, ours words that at once define and confound us.

A Door with a Voice

by Katie Manning

Agape Editions, 2016, $free [digital]

ISBN 978193967528

Grace Gardiner is an MFA candidate in poetry at the University of North Carolina Greensboro and an editor for The Greensboro Review. Her work has appeared in The Adroit Journal, burntdistrict, and Forty Eighty-Five.

http://www.sundresspublications.com/agape/adoorwithavoice.pdf