Review by Hannah Cohen

Review by Hannah Cohen

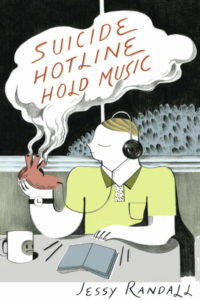

The Atari centipede, Paris, walkie-talkies, and poorly-drawn comics—Jessy Randall’s third collection Suicide Hotline Hold Music is as far-ranging in its topics and images of love, sex, and adulthood as it is humorous and wholly human. A unique aspect of this book is its inclusion of drawings; for the most part, these one-page comics provide an enjoyable, visual experience.

A curator of special collections at Colorado College, Jessy Randall has published in Poetry, Rattle, Asimov’s, Mudfish, McSweeney’s and elsewhere; her first collection A Day in Boyland was a finalist for the Colorado Book Award. A writer with an established and vibrant background, Randall is able to depict absurdity in the mundane (and vice versa) without suffering from heavy-handedness. Her playful outlook manifests into paragraph blocks, pantoums, and a “FUCK YOU” made up entirely of the words “I love you.”

The titular poem introduces the emotional atmosphere of the entire collection in its beginning stanza: “cheerful but not too cheerful” (13). We’re guided through a suicide hotline center, a falafel stand in New York, and even a modern critique of the Rapunzel story. These elements seem unrelated at first read, but by the final poem, themes of growing up and acceptance become apparent.

A personal favorite and arguably one of the stand-outs, “Dreams I Have Had About Spike From Buffy the Vampire Slayer,” shows us scenes of an imaginary romantic relationship with the fictional character—the narrator assumes identities as Buffy, as Buffy’s friend, and even as her own self dating Spike. The real power of this poem doesn’t lie in the pop culture reference; rather it resides in how Spike serves as a catalyst for deeper introspection:

The more dreams I have about Spike, the more I am likely to have. The

dreams do not forget each other. They are connected, like book chapters.

Sometimes I wake up from a Spike dream and remember other dreams

from other nights, dreams I have not remembered before. (44)

With this in mind, we’re given a sense of anxiety in reference to dreams and sleep throughout the collection, such as how “[she]hates falling asleep at night, and dreaming” (38) and “[n]o one speaks here …/ the rendering of voices in a dream” (62). Randall’s ability to trick us into accepting the unusual while giving pause to think about the why is absolutely masterful.

Suicide Hotline Hold Music does have its share of not-so-funny poems, such as “Voices from the Past,” “Is It Ok to Cry at Work.” and “Spontaneous,” which all exist in the internal, less surreal world. Nothing is sugarcoated about the complicated feelings of inadequacy, from “I could be / if I wanted to. / I could just up and … / well, no, I couldn’t” (28) to “[i]t’s almost impossible to / be yourself” (94).

A major theme of this collection is relationships and love—there are a few poems about the husband, such as in the aptly titled “Husband”: “It’s a collage / of love and craving. Let’s go back / to the movie theater where / we put up the arm rest…/ I’m yours” (54). The illustration that accompanies “Husband” is a simple line drawing about a “very easy maze”, which emphasizes the connection. This sort of saccharine teen-like affection appears in other poems, such as a drawing of a chocolate box labeling types of boyfriends, “want[ing]to drink your backwash” (16), and “Dream of the Avant-Garde”: “Brilliant! said everyone. Genius! / And I agreed, and we kissed / like middle schoolers” (65). There’s a beautifully funny prose piece that takes its title from 1 Corinthians 13:4, comparing love to “the smell of bacon frying” (37), making something as clichéd and all-encompassing more personal to the speaker and reader.

Perfectly disjointed, one may consider that the latter section of the book has a noticeable shift towards motherhood and children without much pacing, as seen in her poems about futuristic toys in “Toys of the Future,” the body after childbirth in “How My Anatomy Has Changed,” and her too-true illustration of the “Nine Circles of Motherhood Hell.” However, the fears and joys of parenthood echo an earlier poem: “why / we have children: to put them through it, to find out” (22). Also noticeable is the use of speech bubbles and dialogue in her drawings, something not presented in previous illustrations. Sketches of post-partum depression, the unknowns of caring for a sick child and the internal conflict of saying yes/no—moments we can all relate to whether we’re parents or not.

Suicide Hotline Hold Music is comforting in its honest strangeness, and succeeds in the togetherness of text and pictures. This collection may not appeal to the conventional reader, but for those who like the weird and playful, Randall’s poetry provides an unconventional approach on how to deal with what life gives us.

Suicide Hotline Hold Music

by Jessy Randall

Red Hen Press, April 2016, $11.95 [paper]

ISBN 9781597097260

96pp

Hannah Cohen lives in Virginia and is a MFA candidate at Queens University of Charlotte. She’s the Poetry Editor of Firefly Magazine. Recent work has appeared or is forthcoming in Public Pool, The Shallow Ends, Unlost Journal, and elsewhere.